Celebrating Those Who Have Served Our Country

From St. George’s Episcopal Church, Germantown

Since St. George’s plays host to the 35th annual Massing of the Colors this year, I was tasked to showcase some of the veterans within our parish for that event and for Veteran’s Day the following week.

I was lucky and honored to speak with 12 men over the past three months who have served from World War II to Operation Desert Storm in all sorts of capacities.

Obviously, I have not spoken with every veteran in this parish. With over 50 past and current servicemen and women in the congregation connecting with everyone would have been a tall task. And probably none of you would want to read 50-plus features. So I present to you a mere six instead.

For those to whom I have not yet spoken, you are not forgotten. There will be more opportunities in the future for us to chat and for me to write about you if you’d like. But for now, these six stories serve as a proxy, and I hope they do you all justice.

Before we begin, I’d like to point out two notes from research that I could not add into the other stories.

First, I want to recognize Second Lieutenant Elias Haizlip, who died during his service in World War II. He was the only military member of the parish I found who had made the ultimate sacrifice for his country. On a plaque of past military men that resides in the St. George’s offices, his name alone bears a gold star. He died non-battle, one of more than 90,000 soldiers who did so during WWII.

Second, I want to highlight the efforts of two young men who currently serve: Christopher Walker with the U.S. Army and Daniel Camuti with the U.S. Navy. Coincidentally, I was a classmate with both of these young men at Memphis University School. Chris was a captain and a teammate of mine on the track and cross-country teams and Daniel graduated with my class in 2013 and was (and probably still is) an excellent soccer player.

I extend a huge thank you to everyone who allowed me to write about them and even greater thanks for their sacrifice and service.

— Mac Trammell

Otto Lyons, Jr.

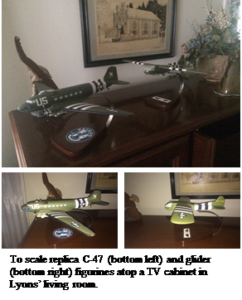

Otto Lyons, left, celebrates his 96th birthday with Ted Morley.

Otto Franklin Lyons Jr. helped liberate Eastern Holland from Nazi Germany in 1944. He flew a glider—not quite a plane, but maybe the next closest thing—into the Netherlands near the German border and spent four nights constantly bombarded by mortars on the front line.

A lifetime later, he sits with two visitors in his white house on Poplar Pike in Germantown, Tenn. about three minutes from the church he in a small way helped found. Decorative plates painted with hunting scenes adorn the walls and mantle of his kitchen. In his wall-to-wall carpeted living room, he puts aside his walker and sits in an oft-used blue chair while telling his visitors all types of stories.

“Don’t you love Otto’s stories?” Stan Sampson, a veteran of the Navy and member of St. George’s Episcopal Church, asked unprompted in an unrelated and separate interview.

Lyons is at once captivating, commanding the gravity of the room, and occasionally droning, prone to start a story but not finish it; a tangent or two may divert the primary narrative, knocking him off track. These sidebars and unfinished tales aren’t unexpected for a man of 96 years, yet the amalgamation of these incomplete memories provides a more detailed, broader, rich story than the otherwise straight telling may have. His silences are pregnant, full of memories he has to choose from to articulate.

You could sit there for hours and listen to Lyons with minimal interruption, save for a fit of coughing or a light, mid-story nap. He would enjoy nothing more than to regale you with stories, mostly because he has few if any outlets for human interaction. His wife, Nadine, of 72 years passed more than two years ago in the summer of 2016. He has since lived with his son, who works long hours away from home, in the house he’s called home since he was 12 years old.

“I sit here several days a week and look at these four walls. And I don’t have anybody to talk to,” he said. “And I’m afraid I’ve gotten into the habit that if I got somebody in here to listen to me that I start talking and don’t know when to shut my big mouth.”

Ask him if he’s lonely though, and he responds, “I get lonely for my wife.” You could read a lot into that answer. It’s probably a way for the tough World War II vet to say yes without copping to being emotionally vulnerable. It may indeed be a defiant “no, but…” that shows the slightest bit of appropriate familial love while also deflecting the question’s negative implication. Either way, the statement is 100 percent truth on its surface; he misses his wife, and he loves to talk about her.

Take the story of how they met. Lyons was training to become a pilot in the Army Air Corps (a precursor to the Air Force), like his father had been in the previous world conflict, in Lubbock, Texas. On a Saturday afternoon, he had gone into town by himself, standing on the corner of Broadway and Avenue Q when… well, it’s better, really, if he tells it.

“I was standing there by myself,” he begins “and this car pulls up, and a girl hops out and runs in the drug store there—it was Hall’s Drug Store. And she comes back out and she says, ‘he might not be home; he don’t answer the phone.’ Somebody else in the car said, ‘well we need another man!’ And somebody said, ‘get him!’

“I looked around,” he continued. “I was the only ‘him’ standing there. They grab me and pulled me in the car and said, ‘you’re going with us!’ I said, ‘wait a minute!’ But there was no ‘wait a minute’ about it.”

He smiles while recounting the story, laughing at intervals. The friendly kidnappers took him to Mackenzie Park near downtown for a picnic, where he had an inauspicious encounter with his future wife.

“That’s where I met her,” he said. “She thought I was a smarty. She didn’t have much to do with me when we were down there.”

But Nadine’s sister seemed to like him. So he took her to the movies a few times, and one Saturday he called to see if she’d like to see another. She said yes, but that she had a babysitting commitment she couldn’t dodge.

“She said, ‘maybe Nadine would like to go with you.’ And I thought, ‘Ohhhh no! Not after what she had to say about me.’” Here, he chuckles and continues, “I said, ‘ain’t no way in HECK she’s going to go with me.’ But sure enough, she came to the phone and said she’d go with me.

“So we went together from then on.”

The two married on Nov. 10, 1943 at St. Paul’s on the Plains Episcopal Church in Lubbock before Lyons left for the European theatre shortly thereafter.

After the War, they moved to Germantown, into the white house on Poplar Pike his family built in 1934 (the property cost $134 and came with three cows, according to Lyons). A lifelong Episcopalian, he had been going to St. John’s with his family until they made the move out east. St. George’s had barely existed before the family soon became members.

After the War, they moved to Germantown, into the white house on Poplar Pike his family built in 1934 (the property cost $134 and came with three cows, according to Lyons). A lifelong Episcopalian, he had been going to St. John’s with his family until they made the move out east. St. George’s had barely existed before the family soon became members.

“[St. George’s] came and asked us if we wouldn’t help them,” Lyons said. “We said, ‘Sure.’ At least my mother did. She was speaking for all of us.”

At first they held services out of the bottom of a Masonic building. But before too long, they built a small chapel, and later the church moved to a site on Poplar Avenue, where St. George’s Independent School now sits. Lyons was the crucifer the day that chapel was consecrated and likewise was an acolyte when it was decommissioned.

“When they built that chapel—the first service when the bishop came out to consecrate it—I was the acolyte,” he said. “I lit the candles the first time in that building… And then when we moved from over Poplar, I was an acolyte [again]—I extinguished the candles for the last time.”

At 84 years and counting, Lyons is the longest tenured member of St. George’s, having seen the parish inhabit four separate spaces of worship from its inception.

And while he has seen his home parish grow from its infancy into what it is today, he has, on the other hand, seen the destruction of churches in a fraction of as much time a world away.

“Don’t ask—do not—ask a serviceman how many men he killed or about how many he killed… Just leave that out,” he implored, unprompted. “That’s the reason why you hear children say, ‘My dad wouldn’t say anything to me about the war.’ A lot of [veterans] are not proud to have been in a war.

“They were, but they weren’t,” he continued. “They were proud, I guess, to serve their country. But they weren’t proud that they had to go out and shoot somebody or shoot at somebody.”

Lyons was a part of Operation Market Garden, a failed attempt by the Allies to break through the Nazi line near the German border. The plan was to drop paratroopers and supplies into the Netherlands and secure nine bridges that would eventually allow British tanks to cross the Rhine River, infiltrating Germany.

Lyons was a part of Operation Market Garden, a failed attempt by the Allies to break through the Nazi line near the German border. The plan was to drop paratroopers and supplies into the Netherlands and secure nine bridges that would eventually allow British tanks to cross the Rhine River, infiltrating Germany.

He flew his glider full of 15 men, machine guns, and mortars into a field near Groesbeek and was immediately sent to defend a bridge in Nijmegen where he and his unit met German resistance.

“I spent about four nights up there on the front,” he said. “And we were shelled with mortars by 88’s during the night. I remember that very well.”

They had to wait for slow-moving British armored vehicles to approach from the South to provide relief. Once they got there, Lyons was pulled away from the main fighting and eventually sent back to France.

When asked how he felt recounting stories like this one, Lyons gave another cryptic answer. “I saw a whole lot more than I wanted to. I’ll just put it to you that way.”

He has too much time to think about these things. Then again, he has a full life’s worth of memories he can toggle through if he’d rather not remember certain things. More than an hour after their arrival, Lyons’ two visitors signal that they must leave him with these thoughts. Lyons, the graceful host, thanks them and for one brief moment lets his guard down.

“It’s such a pleasure having you here,” he says. “It’s just… I just can’t think of everything to try to help you. I just want to talk and talk,” his voice trails off, wistfully.

The other days of that week he’ll get up in the morning, eat a couple of meals, then go back to bed at night. He’ll sit in his blue chair, sometimes watching television, sometimes napping, almost certainly in solitude. The stories and thoughts that cross his mind build with an ever-growing tension, waiting for someone to whom he can tell these tales.

He will wait patiently; his military experience has taught him to do so. It has also taught him the merits of camaraderie, empathy, and selflessness.

“It teaches discipline. And endurance” he explained. “It teaches you to look out for your fellow man, to have some sense of, whether you know him or not, to help him if he needs help.”

ROMEO's

(From left: James Bond, Gus Wadlington, P.Z. Horton, Kenneth Wied, Bill Bettison, Bob White, & George Freeman)

Just about everything you need to know about the ROMEO’s can be discerned from the anagram for which the group’s name stands: Retired Old Men Eating Out.

The self-deprecating humor of the name—augmented by the ironic allusion to the great young Shakespearian lover (they more resemble a group of watered down Red Forman’s)—perfectly captures the essence of this group. They are indeed mostly retired. It is true they have aged past their youths. And when a reporter met them some weeks ago it was in fact while they were enjoying a meal out on the town.

When the reporter found the men in the back of a Perkins on Germantown Parkway, he hadn’t even had a chance to shake hands and say hello before someone chirped about how much hair the boy had. Across the table someone countered that he’d kill to have a head of hair like that. Upon making himself vulnerable, the table pounced on their friend, quipping that he sure could use a few more hairs up there, that they couldn’t remember the last time they saw a hair on top of his head to which the subject summarily had to agree.

This interaction was quintessential ROMEO fair. Their playful ribbing comes from a place of friendship, almost fraternal in nature despite the fact that the range of the seven men’s ages spans at least a generation. They are light with their barbs, knowing that for every teasing comment they dish out, eventually one will aim back at them. The group’s camaraderie is pervasive, probably stemming from something else they all share in common (but not explicit in the group’s name).

These seven men all served in the United States Armed Forces: Gus Waddlington in the Army Air Corps [precursor to the Air Force] from 1944-46; Bill Bettison, an engineer for the Army in the 50’s; Kenneth Wied a private in the U.S. Army from 1956-58; George Freeman a commander in the Navy between 1961-80; P.Z. Horton in the Air Force from 1965-69 before serving in the international guard for almost 30 years; James Bond, fittingly, a counterintelligence officer with the U.S. Army in Korea before spending more than three decades in the reserves; and Bob White, a naval captain for four-plus years before serving in the reserves for another 20-25 years in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps [essentially like a military lawyer].

They may not have shared the same experiences in similar times, places, or circumstances. But they share a fundamental understanding of what kind of sacrifice each of the others made to keep their homes safe. It was an obligation, both Wied and Horton explained without exactly explaining what that obligation was. White chipped in that it was a patriotic sense of duty. Waddlington said that in his case there was no question, no thought. He just went. After all, the world was at war at the time.

Their relationship exists paradoxically as a communal and exclusive sentiment, intimately personal yet something they all understand on an innate level. It affords them an immediate and close bond that is hard to replicate under any other circumstance. And so they use that connection to make themselves laugh, occasionally at their peers’ expense, occasionally at their own, but to the delight of all.

Wayne Carpenter

Sherry and Wayne Carpenter

Wayne Carpenter doesn’t know where his military uniform is. The last he remembers of it was Christmas Day 1969, the day his wife picked him up in Jackson, Miss. after his tour of duty in Vietnam ended.

He had flown across the Pacific the day before, reaching Seattle looking for a military standby ticket back to Mississippi, unaware of the divisive political environment into which he was stepping. Even if he hadn’t been wearing his uniform, he would have stuck out like a sore thumb. Who else would have that dark a tan around the Pacific Northwest in late December? He was marked regardless.

Carpenter, now 75, was supposed to receive a half price flight that day in thanks for his military service. Both the porter at the ticket counter and his supervisor denied this of Carpenter, so the soldier instead paid full price. Protesters yelled at him and other servicemen as they walked out to their planes. When he finally got into his wife’s car in Jackson, he took off his uniform for what would become the last time, in order to avoid any further perceived prejudice from a populace whose righteous anger was directed at the wrong people, at the boys who had no choice but to follow orders, who had been conscripted into a fight that their leaders knew was futile but persisted with anyways in order to retain ever-decreasing shreds of political capital.

Americans at home wanted the war to end. So too, by this point, did many of the G.I’s in the field, many of whom had been drafted (that is to say, did not choose to fight for the cause). Carpenter knew the draft would come for him, so rather than wait for that inevitable end, he signed up with the U.S. Army. Instead of heading to Southeast Asia after completing basic training, he flew to Germany in 1968 where he was part of the 86th artillery unit.

By 1969, however, he could avoid Vietnam no longer, joining the 198th infantry brigade which was holed up in 17 bunkers, 3 men per, tucked into a ridge of mountains by the seashore as a flat rice paddy extended out into the distance.

Because of his work in the 86th artillery unit in Germany (which oversaw nuclear-tipped Pershing missiles, presumably in case the Cold War ever got hot), Carpenter had a higher security clearance than the rest of his brigade. As a result, he handled “Officer of the Day” duties as a sergeant, a peculiar arrangement for a non-commissioned officer, but one he was nonetheless capable of fulfilling.

Though he did not have to venture into the jungle nor engage with the North Vietnamese directly, he knew that his role of communicating via radio with bands of Army Rangers scouting out their enemy was nevertheless a dangerous one.

“They had blown up the Officer of the Day the year before,” he explained in an interview with a reporter. “So I never gave away my position. I didn’t put up my radio antenna until the sun went down… If you put that antenna up they knew where you were… If they know that I command 17 bunkers—”

“That makes you a target,” the reporter interjected.

“The best target!” Carpenter replied. “The thing the Vietnamese did—we did it to England during the Revolutionary War…” Here, he amended his statement. “[In] every war, it has been that sharp shooters shoot officers. So if you do anything that separates or identifies you as a command person, you’re the best person to shoot.”

It could have been easy to crack under the pressure of this knowledge, to begin to preserve one’s own self-interest at the expense of the men he was supposed to protect. But Carpenter kept his cool, making sure to protect himself not at the expense of his fellow soldiers, but in order to continue keeping those men safe. Without him, he said, they would have functioned like a football team without a quarterback.

“I just felt like [17 bunkers of men] weren’t worth anything if I wasn’t capable of doing whatever I did,” he said.

Balancing his self-preservation with the duty he owed to his servicemen, keeping calm while in the midst of increasing pressure was no easy task. But he harkened back to advice one of his father’s friends gave him before he left for war.

“It’s the secret between staying logical [and] being in control,” Carpenter said. “If you’re commanding troops you have to move forward with a certain amount of confidence… Part of putting faith into work is action, [and] blind action is dumb.”

Days later, he reinforces this last statement, sending a message to the effect of “faith can help you do all sorts of things you didn’t think you could do.” He attributes his faith to allowing him to keep his wits in hectic times, to keeping him grounded in the moments of most upheaval.

Like when he was being heckled on his way to his plane in Seattle.

Faith didn’t protect him from feeling mistreated, from feeling, as he understated, “not good.” But it got him that far at the bare minimum, better than many of his contemporaries as he well knows.

“We’ve had a lot of people who’ve gone before us and done a lot that enabled us to have what we have,” he said. “And it wasn’t free.”

So he kept his head down, finishing his pharmaceutical studies, moving to Memphis, and eventually becoming the Director of Pharmacy at St. Francis Hospital. Despite physical and psychoanalytical roadblocks, Carpenter has succeeded. He doesn’t shy away from the tough memories, but he knows their place and knows that he need no longer dwell on them.

With these, as with other moments from his life, Carpenter has followed a guiding principal, founded in faith, which has led him to success. What happens when life throws all it’s got at you?

“I think you rise to the occasion.”

Van Conaway, Sr.

Van Conaway

It’s hard to imagine that of all the emotions you might feel going into a battle, fear would not be one of them.

According to 98 year-old World War II Navy veteran Van Cavett Conaway Sr., he didn’t, and neither did his shipmates as they made invasions in both the European and Pacific theatres.

“I didn’t think a lot about danger. I thought I would return home,” Conaway said in an interview with his grandson years ago. “I never gave a lot of thought to getting hurt or killed or injured. That didn’t really cross my mind. And most of my colleagues out there didn’t either. We thought we’d get home. We know we had to do a job, and that’s what we did.”

Conaway was a 21 year-old student at Mississippi State University when the attack on Pearl Harbor jolted the United States into a worldwide war. He decided to sign up for the Navy, bouncing between Chicago and Millington, Tenn. for his training before heading to Norfolk, Va. to board the USS Procyon in 1943. However, he wasn’t exactly ready to fight.

“They did not train me too well for the war,” he said. Luckily, he quickly learned how to live like a soldier. “You did your own after you got involved. I did. I got acclimated pretty well to it… I got to where I didn’t mind it as long as I had to be there.”

The Procyon was an AKA-2 attack cargo ship, meaning that it was meant to ferry supplies to and from designated areas, but could fend off attacks (or indeed, instigate them) if push came to shove. Conaway was a storekeeper aboard the ship, but also manned the crow’s nest.

“The crow’s nest was up in the air probably 50 feet or more,” he said. “And I’d climb up that pole and sit in that little turret where you could look around and see if anything was coming for a long distance.”

When the Procyon landed in southern France after D Day, he had naught to look out for. The Germans had already fled, retreating to the Siegfried line along the Rhine River and into Northern Italy. After dropping their supplies, Conaway and the Procyon rerouted to the Pacific where they would fight the Japanese at Okinawa in one of the Pacific’s bloodiest and most ferocious battles.

Here, Conaway moved from his position in the crow’s nest to a 44mm. gun, shooting Japanese kamikazes hurtling towards the Procyon and other Allied ships.

“We fired, hit a couple, and they went past our ship into the water,” he recalled. “But there were a lot of ships with us there. You could just see them. They were just everywhere. And these planes were falling in between these ships. Fortunately we didn’t see them hit a ship. Of course they did hit some during the war.”

In fact, many did during that very battle; Okinawa saw one of the largest kamikaze efforts of the war.

While Conaway didn’t see a kamikaze strike a ship, he was able to see something striking about the planes: their pilots.

“[They were] very close. Flew right over us,” he said. “You could see them in the plane it was so close. They were trying to hit us, but we were firing at them. Really, they looked like, for all we could see, they were either dead or they were so wild or something you didn’t know what they were. They just looked dazed.”

It is at this moment that Conaway’s stated lack of fear stands in its most stark contrast. With kamikaze’s flying overhead, so close that one could see the pilot inside, how could one not be scared? Or at least, how could one not look back on that memory without fear?

Maybe it comes back to that line, “We know we had to do a job, and that’s what we did.” Something about burying one’s own self-preservation for the protection of an idea, a family, a nation, and in this case, the lone world on which we live; something of the dismissal of fear in the face of abject terror for a cause you know to be greater than one’s self; something about duty, loyalty, and uncompromised morals becomes apparent from this otherwise straightforward cliché.

It’s what soldiers do. They sacrifice an unprecedented amount and then act like they were just doing their job. Which they were. But of course, it’s so much more than that.

So ask Van Conaway if he ever succumbed to the frights of war, and he’ll tell you no. Whether or not that’s true is irrelevant. The truth, for him, is this:

“We felt like we were fortunate to be able to serve and help our government stay free,” he said. “We knew this was necessary.”

Oswell Person

Oswell Person

“My grandmother told me one time, she said, ‘No matter where you go, God’s there.’”

At the time, Oswell Person didn’t know how prescient of a statement this would be. As a young boy growing up in Bryan, Texas, he couldn’t foresee the many cities and states he’d eventually inhabit nor the “critical” role that faith would play in his life.

When asked in which states he HADN’T lived, Person, in a smooth bass voice that sounds like the essence of 1970’s cool, began to list some, New York and Pennsylvania, for example. Until he realized, he HAD in fact lived in Pennsylvania, briefly teaching there.

Other places Person has lived and worked include: California, Michigan, Maryland, Washington D.C., Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Oregon, Hawaii, Midway Island, Japan, and finally Tennessee.

“We were all over the place, man.”

Person, 79, credits his map hopping and also his education to his military experience. He served with three branches, the Army reserves, Navy, and Air Force reserves, for a combined 13 years over a 35-year span beginning when he was 17 and ending at age 52.

As an African American man in the 50’s and 60’s, he experienced some forms of institutional racism despite his military status. In West Virginia and Arkansas when his unit got some free time to go into town, he had to go to different parts of town than white members of his unit. And in Alexandria, Va. he bought a coffee that he was told he had to drink outside in the cold rather than indoors.

Yet when asked what it meant to him to serve his country, especially as a person of color, Person acted genuinely surprised by the question.

“I never thought about it that way,” he said, almost in a revelatory tone. “I took the same oath that everybody else took. To serve and defend.”

In a time in which racial diversity has become so polarizing yet at the same time so cherished, it was out of the ordinary to hear this response. He regarded himself as just the same as any of his other servicemen and women.

“For the most part, maybe it was naiveté, I never let any of that deter me.”

He credits this positive attitude to his mother, who instilled in him a desire to find and follow the straight and narrow path.

“My mother taught me you have to do what’s right no matter what others do. And you always look for the good in situations, although they would be pretty terrible. If you can do that, you’re better off when one does that [than] if one doesn’t. I’m almost certain that what she shared played into that [self-described naiveté].”

His mother’s teachings helped him realize the importance of his grandmother’s message. While he served, he spent every Sunday in a chapel no matter where he was. In Japan, a local church would often ask the Navy for assistance, and Person frequently volunteered. He recollects becoming an Episcopalian around 1981, about three years before he entered the Air Force reserves.

Person was fortunate that he did not have to fight during his time in the military, though he was in the Navy during the beginning of the Vietnam War and the Air Force during Desert Storm. For this, and for the many opportunities—financial, educational, travel, or otherwise—he says his time with the U.S. Armed Forces “couldn’t have turned out any better.”

Of course, raised with such a positive outlook to disregard the negatives and gain strength from any upside, it was only natural for Person to think this way. He has focused on doing the right thing, and he has never regretted it.

“Always try to do what’s right, whether you’re in the military or not,” he said. “And I think when you do that, things work out for you.”

Stan Sampson

Stan and Glynis Sampson

How many of us knew exactly what we wanted to be when we grew up? How many of us still, to whatever extent, aren’t sure of what we’d like to be?

Not Stan Sampson. Ever since he was a boy living in California, he’s known he wanted to fly planes.

“When I was in school,” he said, “I used to sit out by the airport, by the runway and watch the airplanes taking off and landing and do homework in my car because I just like sitting there. And I just thought ‘You know what? That’s what I’m going to do.’”

And he has, flying for FedEx for almost 30 years. But he couldn’t have gotten to where he was without having flown communications planes for the Navy in the 80’s.

“[Flying missions] was really good for me because I was young at the time and we had to have an airplane in the air 24 hours a day, 24/7, always. So I got to fly a lot.”

He was flying EC 130’s based out of Hawaii on ten or 12-hour missions, communicating with underwater nuclear ballistic missile submarines.

“They’re underwater the whole time, so who’s going to tell them if they ever have to shoot their missiles off? That was our job.”

Those subs stayed underwater for 3 months at a time, so in addition to sending top-secret, coded messages that even Sampson and his crew didn’t understand, they also tried to update the submarine inhabitants with news and sports.

“Sometimes we’d just go out there and give them the score of the Super Bowl.”

Fortunately for Sampson, he never had to send any doom-ridden signals, even though the Cold War was well underway. His son, Christopher, a combat veteran himself, sometimes jabs his father about the lack of action he saw during his time with the Navy.

“My son likes to call me the Cold War veteran. It’s funny because it’s kind of a backhanded compliment,” Stan said. “I was lucky enough to be part of the service when I didn’t have to do any of that. The reality is, that’s a great thing.”

Christopher, an Air Force pilot who has served multiple tours of duty in the Middle East, jokes, according to Stan, that he ought to get his dad a ‘Cold War Veteran’ hat or bumper sticker. “The reality is,” Stan admits, “I would be proud of that. Actually, I kind of wish he would buy me that hat, because I would like to wear that.”

That’s exactly the kind of thing you’d expect this laid back California man to say. He frequently wears Hawaiian shirts not only because they’re comfortable, but also because they remind him of Catalina Island, Calif. where he grew up.

He’s parlayed that relaxed vibe with one of humility. For example, he wanted to make sure at the beginning of an interview with a reporter that he highlighted other members of the St. George’s Episcopal Church congregation who had served in the armed forces whom he believed deserved to be profiled as well. Then, at the end of the interview, he bookended the conversation by saying how thankful he was to the Navy and to United States citizens for allowing him to serve.

“Basically I worked for all of you guys while I was doing this,” he said. “I think that I got a whole lot more out of the military than the military got out of me. I’m just very, very thankful for it and blessed that I ended up where I ended up in the Navy.”