During the month of December, The Gallery is hosting a Diocesan art exhibit – in honor of Bishop Johnson. Below are biographical sketches of eight of these extraordinarily talented Diocesan artists written by Mac Trammell Youth/Communications Ministry Coordinator at St. George’s. Please visit The Gallery and see works of these Diocesan artists, including several members of our parish family. The exhibit includes pieces ranging in form from thrown clay to photography to abstract and traditional painting.

Sherry Lane and Wayne Carpenter

Southern Camellia by Sherry Lane Carpenter

Painting of a German Town by Wayne Carpenter

Sherry Lane and Wayne Carpenter serve as each other’s critics.

While in some relationships this might be a hindrance, for these two artists it’s an asset.

“We’ll go to each other and say, ‘Well what do you think about [this]?’” Sherry Lane said. “We kind of use each other to bounce ideas off of. If something doesn’t seem to be working out, [one of us will ask] ‘Do you think I should do this or that?’”

Once a suggestion has been given, the critic, however, lets the artist finish the work however she or he wants. Wayne, after admitting he probably couldn’t stand that type of brutal honesty from everyone, compared their criticisms of each other’s works to ballroom dancing.

“It would be like if you’ve got a dance partner and you’re learning a new thing,” he said. “You have to work with the other person. And part of it would be some critique of how you’re moving, what you’re doing.”

The two have been painting for a long time. Sherry Lane, who used to work for businesses doing office work, began before she was married and described her style as more defined with aspects of fluidity. Wayne, who tends to capture broader scenes in a more fluid way, started painting when Sherry Lane sent him a watercolor set in Vietnam. The retired Director of Pharmacy at St. Francis hospital painted at night as a diversion from the mundane and sometimes haunting work he was doing in the war, finishing 15 or 20 pieces while he was there.

The two Mississippians had been life-long Methodists when Missy George invited them to show at an exhibition at St. George’s Episcopal Church. They started going to church there on Sundays, becoming so enraptured by the space and the people within it that they were confirmed into the Episcopal Church in December 2016.

One of the challenges Wayne in particular faces is attempting to elicit a specific emotion from his art’s viewer. Working with and against this hurdle has taught him the value of patience and perspective.

“Sometimes you try to express something from a piece of art that’s not just painting its surface,” he explained, “but you’re trying to express some emotion, some something that’s going on. If it’s a person you’re trying to do that. Sometimes you don’t. You just don’t get it right. If you’re looking at a person, maybe just the way you do their eyes tells where they are. You try to do things. You don’t always succeed. You have to accept your failures and move on.”

Cherie Robinson

A Cotton Field by Cherie Robinson

A shack in a snowy wood by Cherie Robinson

A few years back an unfamiliar looking high school aged boy approached Cherie Robinson.

“I know you,” the boy claimed, though Robinson could not remember him. He introduced himself, telling the 51 year-old specialty pharmacist that she had spoken at his elementary school years before. Indeed she had, along with her friend and the author of the children’s book, The Adventures of Abbey O’Hagan, which Robinson had illustrated.

The boy remembered her because her presentation was about her illustrations. The boy remembered her because he was an artist too.

“I was like, ‘Wow…’” she said of that moment. She had not considered the breadth and reach of her work, but his response allowed her to process that her work had been an inspiration.

“In that way, my art touched a lot of kids, a lot of people,” she said, “and encouraged a lot of kids to use their talent.”

Like the boy in her story, Robinson had realized at a young age that she had a talent for art. And also like the boy, she had an inspirational figure to guide that talent.

“We had a great art teacher in high school, in my little school” she said. “She was really the one who inspired me and made me know that I could do it.”

Robinson grew up in Greenville, Miss., and as a result, most of her paintings are of scenes of the Delta.

“I like to paint what make me happy whether it’s a cotton field or a shack out on my dad’s farm,” she said.

She went on to say, “I never paint something that I’ve not seen or that I’ve not witnessed. So every painting to me has a certain meaning.”

Some of her works have included churches, though she admits the trope of Southern churches in Southern art has grown a bit cliché. However, though the content of her works may not include explicit faith themes, she said that the process of painting is like a spiritual exercise.

“Painting just does quiet your soul,” she said. “It’s therapeutic. Just like someone might meditate or just be still, painting makes me still.”

She paints when she can find time. Between her job, her family, and her other hobbies (running, biking, and scrapbooking), she can struggle to find time to express herself artistically.

“That’s the biggest challenge,” she said, “is finding time, making time, not replacing it with something else. That’s the biggest challenge.”

She acknowledges that she has way more ideas than she’ll ever be able to finish, even if time were not an issue. She hopes one day to illustrate another children’s book if she can indeed find the time. But for Robinson, painting is an outlet for expression, an avenue that allows her mind to work in different and meditative ways.

“It makes me relax,” she said “and focus on something beautiful.”

Morgan Brookfield

Judy and Morgan Brookfield

Life Transforming by Morgan Brookfield

“It’s hard for me to believe that someone wants to come talk to me about my painting.”

And yet it is the second time that Morgan Brookfield has allowed a reporter into his home to ask him about his art. Previously, CNN had driven from Atlanta to the retired banker’s home in East Memphis, lugging its extensive camera equipment up to the second floor space Brookfield uses as his studio, which he also shares with his granddaughter as a play space.

His paintings adorn much of the wall space in the room. Their strong colors draw a new viewer’s eyes in multiple directions attempting to ingest the vibrancy of each piece. A work in progress sits upon an easel by a window, waiting to join its brothers and sisters hanging around the room.

Brookfield, 77, has not always been a painter. It’s a hobby which the Nyack, New York born transplant adopted during his retirement. His daughter and his wife encouraged him to take up painting after he spent 35 years in banking at First Tennessee and then with his own merchant-banking firm, Brookfield & Company. During meetings he used to sketch absentmindedly on the back of envelopes or in the margins of his notebook.

He’s translated that penchant for drawing into a substantial expressive tool, saying of his painting that it “has added a significant dimension to my life in a way I never would have expected. And I’m very appreciative of that.”

However, the formidable task of creating something from nothing, of mapping out an idea from the mind to the canvas, stirs Brookfield with apprehension.

“I’m always afraid when I pick up a canvas,” he said. “Every canvas I’m nervous about. It’s sort of overpowering. You take this big white thing and you start putting paint on it. What’s it going to look like?”

Yet he said he believes his art is “God inspired.” Every painting he’s ever done has a different scripture written on the back, and Brookfield characterized himself as “deeply faithful.” He and his wife, Judy, belong to the Church of the Holy Communion where Brookfield has served on the vestry.

Faith doesn’t often manifest itself openly in Brookfield’s work, but one piece which he’s entering into the Diocesan Art Exhibit at St. George’s Episcopal Church is compelling for its representation of faith and for its unusual form.

“Life Transforming” is an oil painting on a hunk of oak wood recovered from a fallen tree in Elmwood Cemetery. Brookfield utilized the reddened and burnt nature of his canvas to imitate the style of one of his favorite artists, Rembrandt. The landscape looks corrugated, burnt or burning as a river meanders through the wreckage. Smoke ascends from the hilly terrain, suffocating the negative space in the middle of the “canvas.”

However, rising from within the smoke and penetrating the upper third of the piece is an angelic, three headed figure, or viewed another way, three celestial bodies shining down into the darkness. The troika represents the hope that can be found in all situations, no matter how dire they may seem, the light at the end of the tunnel that signals freedom from the darkness. And if you look carefully, there appears to be a white angel painted on the bark on the left side of the piece, further cementing its theological themes.

Brookfield never imagined he would create something like this. Nor did he believe he’d create any of his works. “I really thought I would work until I died,” he said. But business changed, moving in a different direction. “Didn’t work out that way, and here I am.”

“I’m extremely happy, and I stay busy every day whether its painting or other things,” he said. “[Judy and I] both are busy. I get to spend a lot of time with the prettiest girl in the world with the biggest heart. What else could you ask for?”

Eileen Cashbaugh

A collage by Eileen Cashbaugh

A collage by Eileen Cashbaugh

Eileen Cashbaugh was sitting in a waiting room, staring at the paintings on the wall.

She wasn’t sitting in just any waiting room. She was at the West Clinic, fighting a breast cancer diagnosis.

Yet she focused on the rotating exhibitions of art that the West Clinic supplied while she sat there. She had won a scholastic award for art as an elementary school student, but had never seriously honed her talent since. As she sat and looked, she began to think to herself, “I might be able to do this.”

Of course, she also meant, ‘beat cancer.’ But her intent was to take up painting, to try something new, to take a risk.

“After you have cancer, you kind of think you don’t have anything to lose,” she said. “You’re a little bit more—or at least for me—I was a little more comfortable taking a risk.”

Without her cancer diagnosis, she never would have taken up painting, an endeavor that’s she’s fallen in love with, wishing she had taken it up years ago. She’s put to use that new lease on life that she claimed from cancer, unwilling to let pressure or insecurity stop her from trying new things and doing what she loves.

“[Cancer] does make you feel that you have been given extra time,” she said. “So you don’t feel you have as much to lose, taking a chance.”

Cashbaugh, 66, began taking classes in 2005, a year after her diagnosis and treatment, and she will admit that painting served not only as a therapeutic exercise, but also as a distraction.

“[Painting] is a very good way to manage anxiety because it ties your brain up,” she said. “It’s problem solving. It forces you to focus on something else. Even when you’re not in front of what you’re working on, it’s still in your mind. So you think about it even when you’re not doing it.

“And it’s also a way to express emotions,” she continued, “even if you’re not aware that that’s what’s going on, that really is what’s going on. For that reason—and it’s little bit physical—I mostly did it as therapy.”

On her website, Cashbaugh, a retired nurse, writes that painting is the single most therapeutic thing she’s done because it envelops her mind, body, and spirit. She elaborated, in an interview, on her spiritual connection with the art, describing it as if it were divinely inspired.

“I often wonder sometimes who has pushed my brush for me,” she said, “especially if something comes out that I’m pleased with. That is a little bit of a miraculous thing to me that you can create something like that and not know where it came from.”

When Cashbaugh begins painting, she doesn’t know what she’s about to produce, saying that she’s more interested in the journey of painting than in the destination.

“I rarely know what I’m going to end up with,” she said. “Some painters have in their mind what they want. I’m more expressive and more intuitive. I’m interested to see what comes out of myself.”

She paints for her own entertainment, or as she wryly puts it, “I do it because I like to push paint around.” She’s moved more into mixed media works and collaging thanks in part to a background in traditional quilting.

Cashbaugh will admit that there’s no grand, cerebral message she wants her works to tell the world. Other than a meek admission of her own defiant strength: “If there’s any statement,” she said, “it’s that I’m still here.”

Melissa Bridgman

A Vase by Melissa Bridgman

The ethos behind Melissa Bridgman’s pottery derives from a short story she read in high school.

“Everyday Use” by Alice Walker tells the story of a poor, rural African American family consisting of a mother and two daughters, the older of whom has big city aspirations. This daughter leaves the farm, but returns one day pretending as if she’s come to spend time with her family when in actuality, she’s come to claim an early inheritance. She asks her mother if she can have some quilts that the matriarchs of their family had woven over generations.

At this request, the mother fumbles, confessing she’s already told her other daughter she can have them. The older daughter exclaims that the quilts are priceless and accuses her sister, predicting she will ruin their value by actually using them.

“‘She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use’ [she said].

“‘I reckon she would,’ [the mother] said. ‘God knows I been saving ‘em for long enough with nobody using ‘em. I hope she will!’”

This interaction is the crux of Walker’s story. Should the older daughter get the quilts, knowing their emotional and functional value will peter out as their monetary and historical value increase? Or should the younger daughter receive them, putting them to their intended use, keeping the family’s tradition and memory alive while causing the quilts to deteriorate physically?

Walker sides with the latter as the mother snatches the quilts away from her elder child and puts them in her younger daughter’s arms. This idea of an object of inspirational utility stuck with Bridgman and affects how and why she makes pottery for a living.

“The work I make is meant to be used,” she explained. “It is not meant to be special occasion work. It is everyday, nice work with a lot of utility so that your everyday life is improved by using things that you love.”

Bridgman makes bowls, plates, mugs, vases and more and almost all of it is decorated with a cobalt blue color. There are functional reasons she uses so much blue (it’s cheaper than red and doesn’t muddy up like green), but she admits that she is captivated by the color, having always been drawn to the sky and large bodies of water.

The Illinois-born, 41 year-old mother of one calls her style illustrative and on occasion uplifting. She knows that sometimes she’s making a piece for someone who is struggling with a marriage, with a job, or with any number of other issues. And it is when one thinks about these customers that the idea from “Everyday Use” really hits home.

“Ceramic work is a medium that is useful,” Bridgman said, “and it can be inspiring and something that people use every day. It’s not just something you admire from afar.”

Caroline Brown

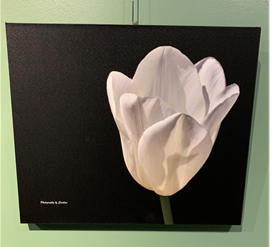

A White Tulip by Caroline Brown

Caroline Brown asked her friend to take a photo of the church she used to attend when she lived in Lexington, Ky. She gave him her camera, and when he handed it back to her, she was aghast at what he had done.

“He cut off the steeple!” she recalled vexingly. “To me that was just… Why? Why would you do that?”

That is to say, the 80 year-old former property manager has a keen eye for composition that begins before an image comes into frame.

“When I look through the viewfinder, I try to compose at that point,” she said. “And I’ve seen people go take a camera and hold it out there and take pictures. I can’t do that. That is so random.”

Brown, a mother of two, wants to capture and highlight the essence of perfection in God’s created nature when she takes a photo. She doesn’t want anything to blend in; she wants the colors to pop in her work.

Consider her three entries into this year’s Diocesan Art Exhibit. Each is a photo of a lone flower against a dark background. One is a red tulip, jutting diagonally across the canvas. Its purple and orange hues starkly contrast with the blackened backdrop on which it rests.

The second is a pink peony which looks as if it’s blooming out of its own frame towards the viewer. Its green stem quickly fades into the distance.

The third is a crisp, white tulip which lies against a rich, black background, as if the flower had fought its way through the darkness to stand defiantly as a beacon of hope amidst its bleak surroundings.

All three are meant to draw the viewer’s attention to their subjects. Details are highly refined but contained to the subject. The negative space is just that: negative. There are no frills or objects to distract you from the colorful bursts in their frames.

And this is precisely how Brown likes them. They are distinct, they are magnetizing, and they are carefully represented.

“I think they’re striking,” Brown said of the photos. “They don’t just look like a plain old tulip sitting in a vase… They have some more drama to them.”

Martha Ann Gossett

Flowers by Martha Ann Gossett

Martha Ann Gossett doesn’t show her work in very many exhibitions. It’s not for a lack of talent or for poor self esteem or even because she doesn’t like to. In fact, it’s for the exact opposite reason.

“I don’t do a lot of exhibition because I don’t want it to become a job,” she said. “I enjoy it so much that I just do things like this show [the Diocesan Art Exhibit] and a few others.

“If I sell in show, occasionally someone will come to my house and buy something,” she continued. Here, her husband, Larry, of 52 years jumps in. “Last show she was in, everything was not for sale,” he said.

“I had offers,” Martha Ann explained. Yet, she couldn’t bear to part with her work. “I like [my paintings]! I want to keep them!”

Though she is now painting, the 77 year-old mother of two has always been good with her hands. She learned how to sew as a child and has also done a lot of needlepointing. That handiwork evolved into the painting she does today.

Her style is more detailed than impressionistic. “I want to look at something and know it’s a dog,” she said. She and her husband, Larry, watched a documentary about Pablo Picasso, the renowned Spanish painter, whose style is extremely unrealistic. While the couple was floored by his genius, they both agreed that abstraction was not something they appreciated.

“I guess I just like knowing what I’m seeing,” she said.

As such, she generally paints landscapes or occasionally portraits of dogs, aiming to represent her subjects faithfully. When she’s painting a scene in nature, she feels as if she’s capturing the majesty of God’s work in her work.

“Who else but God could create these moments?” she asked of her subjects. “[They tell] me who created it all, where it came from. It’s not just a pretty scene, it’s God’s creation.”

She’s been working on a painting of one of the carousel horses at the Children’s Museum, which she remembers from the old Fairgrounds before they moved. Larry has suggested to her that it looks complete, but being the perfectionist she is, she can’t pull herself away from adding details and minutiae to suit her eye.

However the carousel piece turns out, Martha Ann hopes that it and all her work serves a greater purpose: making others happy.

“I hope [my work] will bring some kind of joy in one form or another to somebody,” she said. “Some sense of pleasure to somebody or everybody, to be idealistic, that sees it.”